Section 10.1 Basic Definitions

¶In Chapter 1 we introduced the concept of the Cartesian product of sets. Let's assume that a person owns three shirts and two pairs of pants. More precisely, let \(A = \{\textrm{blue shirt}, \textrm{tan shirt}, \textrm{mint green shirt}\}\) and \(B = \{\textrm{grey pants}, \textrm{tan pants}\}\text{.}\) Then \(A\times B\) is the set of all six possible combinations of shirts and pants that the individual could wear. However, an individual may wish to restrict themself to combinations which are color coordinated, or “related.” This may not be all possible pairs in \(A\times B\) but will certainly be a subset of \(A\times B\text{.}\) For example, one such subset may be: \(\{(\textrm{blue shirt}, \textrm{grey pants}), (\textrm{blue shirt}, \textrm{tan pants}), (\textrm{mint green shirt}, \textrm{tan pants})\}\text{.}\)

Subsection 10.1.1 Relations Between Two Sets

Definition 10.1.1. Relation.

Let \(A\) and \(B\) be sets. A relation from \(A\) into \(B\) is any subset of \(A\times B\text{.}\)

Example 10.1.2. A simple example.

Let \(A = \{1, 2, 3\}\) and \(B = \{4, 5\}\text{.}\) Then \(\{(1, 4), (2, 4), (3, 5)\}\) is a relation from \(A\) into \(B\text{.}\)

Of course, there are many others we could describe; 64, to be exact.

Example 10.1.3. Divisibility Example.

Let \(A = \{2, 3, 5, 6\}\) and define a relation \(R\) from \(A\) into \(A\) by \((a, b) \in r\) if and only if \(a\) divides evenly into \(b\text{.}\) The set of pairs that qualify for membership is \(r = \{(2, 2), (3, 3), (5, 5), (6, 6), (2, 6), (3, 6)\}\text{.}\)

Subsection 10.1.2 Relations on a Set

Definition 10.1.4. Relation on a Set.

A relation from a set \(A\) into itself is called a relation on \(A\text{.}\)

The relation “divides” in Example 10.1.3 will appear throughout the book. Here is a general definition on the whole set of integers.

Definition 10.1.5. Divides.

Let \(a, b \in \mathbb{Z}\text{,}\) \(a \neq 0\text{.}\) We say that \(a\) divides \(b\text{,}\) denoted \(a \mid b\text{,}\) if and only if there exists an integer \(k\) such that \(a k = b\text{.}\)

Be very careful in writing about the relation “divides.” The vertical line symbol use for this relation, if written carelessly, can look like division. While \(a \mid b\) is either true or false, \(a/b\) is a number.

Based on the equation \(a k = b\text{,}\) we can say that \(a|b\) is equivalent to \(k= \frac{b}{a}\text{,}\) or \(a\) divides evenly into \(b\text{.}\) In fact the “divides” is short for “divides evenly into.” You might find the equation \(k= \frac{b}{a}\) initially easier to understand, but in the long run we will find the equation \(a k = b\) more convenient.

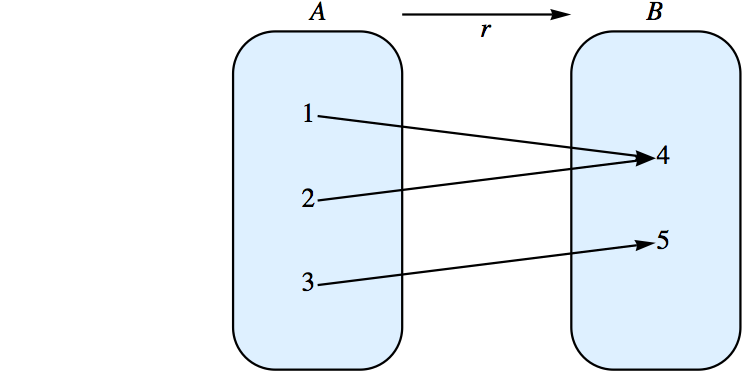

Sometimes it is helpful to illustrate a relation with a graph. Consider Example 10.1.2. A graph of \(R\) can be drawn as in Figure 10.1.6. The arrows indicate that 1 is related to 4 under \(R\text{.}\) Also, 2 is related to 4 under \(R\text{,}\) and 3 is related to 5, while the upper arrow denotes that \(R\) is a relation from the whole set \(A\) into the set \(B\text{.}\)

A typical element in a relation \(R\) is an ordered pair \((x, y)\text{.}\) In some cases, \(R\) can be described by actually listing the pairs which are in \(R\text{,}\) as in the previous examples. This may not be convenient if \(R\) is relatively large. Other notations are used with certain well-known relations. Consider the “less than or equal” relation on the real numbers. We could define it as a set of ordered pairs this way:

However, the notation \(x \leq y\) is clear and self-explanatory; it is a more natural, and hence preferred, notation to use than \((x, y) \in \le\text{.}\)

Many of the relations we will work with “resemble” the relation \(\leq\text{,}\) so \(x R y\) is a common way to express the fact that \(x\) is related to \(y\) through the relation \(R\text{.}\)

Relation Notation Let \(R\) be a relation from a set \(A\) into a set \(B\text{.}\) Then the fact that \((x, y) \in R\) is frequently written \(x R y\text{.}\)

Subsection 10.1.3 Composition of Relations

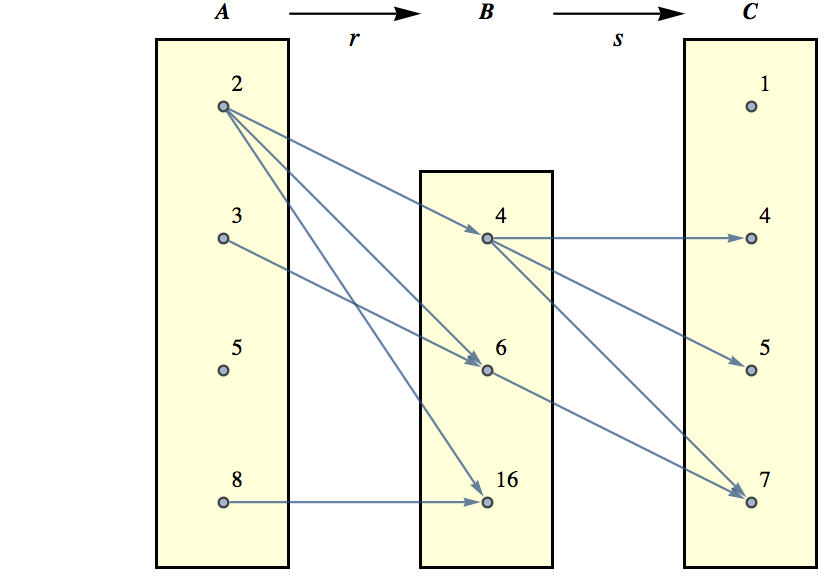

With \(A = \{2, 3, 5, 8\}\text{,}\) \(B = \{4, 6, 16\}\text{,}\) and \(C = \{1, 4, 5, 7\}\text{,}\) let \(R\) be the relation “divides,” from \(A\) into \(B\text{,}\) and let \(S\) be the relation \(\leq\) from \(B\) into \(C\text{.}\) So \(R = \{(2, 4), (2, 6), (2,16), (3, 6), (8, 16)\}\) and \(S = \{(4, 4), (4, 5), (4, 7), (6, 7)\}\text{.}\)

Notice that in Figure 10.1.8 that we can, for certain elements of \(A\text{,}\) go through elements in \(B\) to results in \(C\text{.}\) That is:

| \(2 | 4 \textrm{ and } 4 \leq 4\) |

| \(2 | 4 \textrm{ and } 4 \leq 5\) |

| \(2 | 4 \textrm{ and } 4 \leq 7\) |

| \(2| 6 \textrm{ and } 6 \leq 7\) |

| \(3| 6 \textrm{ and } 6 \leq 7\) |

Based on this observation, we can define a new relation, call it \(RS\text{,}\) from \(A\) into \(C\text{.}\) In order for \((a, c)\) to be in \(RS\text{,}\) it must be possible to travel along a path in Figure 10.1.8 from \(a\) to \(c\text{.}\) In other words, \((a, c) \in rs\) if and only if \((\exists b)_B(a R b \textrm{ and } b S c)\text{.}\) The name \(RS\) was chosen because it reminds us that this new relation was formed by the two previous relations \(R\) and \(S\text{.}\) The complete listing of all elements in \(RS\) is \(\{(2, 4), (2, 5), (2, 7), (3, 7)\}\text{.}\) We summarize in a definition.

Definition 10.1.9. Composition of Relations.

Let \(R\) be a relation from a set \(A\) into a set \(B\text{,}\) and let \(S\) be a relation from \(B\) into a set \(C\text{.}\) The composition of \(R\) with \(S\text{,}\) written \(RS\text{,}\) is the set of pairs of the form \((a, c) \in A\times C\text{,}\) where \((a, c) \in RS\) if and only if there exists \(b \in B\) such that \((a, b) \in R\) and \((b, c) \in S\text{.}\)

Remark: A word of warning to those readers familiar with composition of functions. As indicated above, the traditional way of describing a composition of two relations is \(RS\) where \(R\) is the first relation and \(S\) the second. However, function composition is traditionally expressed in the opposite order: \(S\circ R\text{,}\) where \(R\) is the first function and \(S\) is the second.

Exercises 10.1.4 Exercises

¶1.

For each of the following relations \(R\) defined on \(\mathbb{P}\text{,}\) determine which of the given ordered pairs belong to \(R\)

\(x R y\) iff \(x|y\text{;}\) (2, 3), (2, 4), (2, 8), (2, 17)

\(x R y\) iff \(x \leq y\text{;}\) (2, 3), (3, 2), (2, 4), (5, 8)

\(x R y\) iff \(y =x^2\) ; (1,1), (2, 3), (2, 4), (2, 6)

\((2,4), (2,8)\)

\((2, 3), (2, 4), (5,8)\)

\((1,1), (2,4)\)

2.

The following relations are on \(\{1, 3, 5\}\text{.}\) Let \(R\) be the relation \(x R y\) iff \(y = x + 2\) and \(S\) the relation \(x S y\) iff \(x \leq y\text{.}\)

List all elements in \(RS\text{.}\)

List all elements in \(SR\text{.}\)

Illustrate \(RS\) and \(SR\) via a diagram.

Is the relation \(RS\) equal to the relation \(SR\text{?}\)

3.

Let \(A = \{1,2,3,4,5\}\) and define \(R\) on \(A\) by \(x R y\) iff \(x + 1 = y\text{.}\) We define \(R^2 = R\,R\) and \(R^3 = R^2 R\text{.}\) Find:

\(R\)

\(R^2\)

\(R^3\)

\(R=\{(1,2), (2,3), (3,4), (4,5)\}\)

\(R^2 = \{(1,3), (2,4), (3,5)\}=\{(x,y) : y=x+2, x,y\in A\}\)

\(R^3=\{(1,4), (2,5)\}=\{(x,y) : y=x+3, x,y \in A\}\)

4.

Given \(R\) and \(T\text{,}\) relations on \(\mathbb{Z}\text{,}\) \(R = \{(1, n) : n \in \mathbb{Z}\}\) and \(T= \{(n, 1) : n \in \mathbb{Z}\}\text{,}\) what are \(RT\) and \(TR\text{?}\) Hint: Even when a relation involves infinite sets, you can often get insights into them by drawing partial graphs.

5.

Let \(\rho\) be the relation on the power set, \(\mathcal{P}(S )\text{,}\) of a finite set \(S\) of cardinality \(n\) defined \(\rho\) by \((A,B) \in \rho\) iff \(A\cap B = \emptyset\text{.}\)

Consider the specific case \(n = 3\text{,}\) and determine the cardinality of the set \(\rho\text{.}\)

What is the cardinality of \(\rho\) for an arbitrary \(n\text{?}\) Express your answer in terms of \(n\text{.}\) (Hint: There are three places that each element of S can go in building an element of \(\rho\text{.}\))

When \(n=3\text{,}\) there are 27 pairs in the relation.

Imagine building a pair of disjoint subsets of \(S\text{.}\) For each element of \(S\) there are three places that it can go: into the first set of the ordered pair, into the second set, or into neither set. Therefore the number of pairs in the relation is \(3^n\text{,}\) by the product rule.

6.

Let \(R_1\text{,}\) \(R_2\text{,}\) and \(R_3\) be relations on any set \(A\text{.}\) Prove that if \(R_1\subseteq R_2\) then \(R_1R_3\subseteq R_2R_3\text{.}\)